Bringing Deported Migrants Home to the US

By Robert McKee Irwin

Problem

The vast majority of migrants who get deported from the United States, including those with US citizen spouses or children, are highly unlikely to find a way to return to the country under current law.

Solution

Current immigration laws should be modified to prevent family separation, and to lay out short term legal paths for family reunification for deported migrants whenever possible.

Observations

What does it take for a deported migrant to be readmitted to the US? Only a handful of the over 250 migrants who have shared their stories through the Humanizing Deportation project have been successful in their endeavors to return to the US. A look at their stories offers some insights.

Emma Sánchez, an undocumented Mexican immigrant, married US marine veteran Michael Paulsen in 2000. Six years later, with three young sons to care for, she applied for legal residency as the wife of a US citizen. She was told to bring her paperwork to the US consulate in Ciudad Juárez, where she learned she would not be allowed to return to the US for ten years.

Normally when migrants are processed by immigration authorities for return to their homelands, they are assigned a penalty of anywhere from three years to a lifetime during which they are prohibited from returning to the country.

For the Paulsen family this meant that they would either be moving to Mexico or undergoing a forced family separation for at least ten years. The news was traumatic, and it was shocking to the family that, as Emma puts it, US immigration officials “didn’t care at all; they didn’t care that my husband couldn’t speak Spanish; they didn’t care that he was American.”

The couple struggled to figure out how to parent their children, eventually settling on a plan for Emma to live in Tijuana, and Michael and the couple’s three US citizen sons in San Diego. The four would visit Emma every weekend and spend their vacation time with her in Tijuana. This setup was hard on all of them, as they recount together in the digital story “The Wall Separates Families But Never Feelings” recorded in Tijuana in 2017.

In this video, each of the children give their accounts of what it was like to live for all these years as a transborder family. The kids recall waiting in long lines at the border in the early hours of Monday mornings to try to get to school on time.

Only after ten years could Emma begin an application process to join her family by paying significant fines to “pardon” her prior undocumented status. She finally returned as the spouse of a US citizen and legal permanent resident after twelve and a half years, in late 2018. She and her family tell of this happy ending and their complicated process of readjustment in a second digital story, “Separated by Inflexible Laws, Reunited by Unshakeable Love.”

Héctor Barajas was a legal permanent resident who served in the US military upon graduating from high school in 1995. He was told he would automatically be awarded citizenship for his service to the country, eventually leaving the military with an honorable discharge.

Soon afterwards he was involved in a shooting incident that resulted in a criminal conviction. After serving his sentence, he was surprised to learn that an “immigration hold” had been placed on his file and instead of being released, he was sent to an immigration detention center and deported, a story he tells in “The American Dream? Part I.”

In 2004, the immigration judge told him: “Thank you for your service; if you had been in during wartime I would’ve allowed you to stay here.” Only years later would Barajas figure out that because he had been in service during 9/11, he should have been granted citizenship and protected from deportation.

However, upon being deported to Mexico, a country he had left as a small child, he was lost. He opted to cross back to the United States, undocumented. Crossing the border without legal authorization after having been deported is considered an “illegal reentry” and is classified as an “aggravated felony.”

Barajas managed to get by peacefully for five years, during which time his daughter was born. However, after being involved in a traffic accident, he ended up getting deported for a second time. As he tells in “Part II” of his story, his initial penalty had been twenty years; this time he was deported for life.

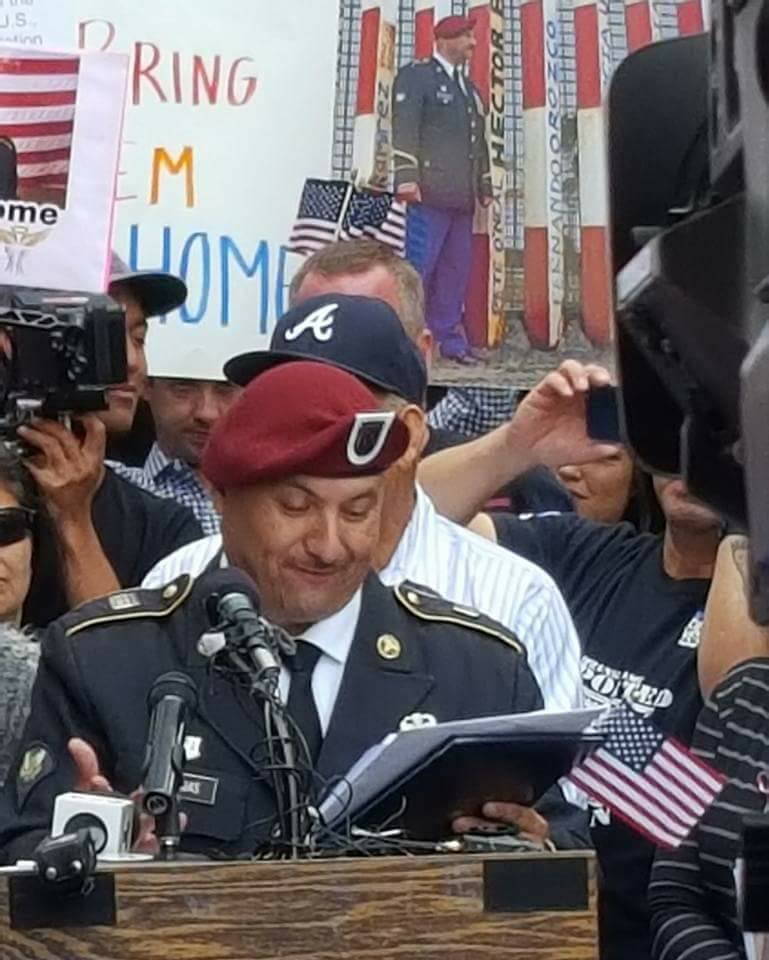

The second deportation was much more painful due to the separation from his small daughter. However, Barajas also had become more resourceful. In Tijuana, he founded an organization, Deported Veterans Support House, that offered support and advocacy for the many US military veterans who have been deported.

His organization works to obtain military benefits, and also works to find legal means to return some deported veterans to the US. In his own case, he was able to obtain a pardon from the California governor. With his record cleared, his deportation was nullified, and in April 2018, Barajas was able to obtain the US citizenship that he should have been granted for his service in 2001.

While his case, which he discusses in “The American Dream for Real,” ended happily eight years after his second deportation, it was anything but simple, requiring multiple pardons. The media visibility he obtained through his advocacy has been helpful in convincing some members of congress to support proposed legislation to put an end to the deportation of military veterans, and to bring others back home.

More recently, the United US Deported Veterans Resource Center, also located in Tijuana, successfully advocated for the readmission of Andy de León, an elderly veteran in need of medical attention. De León tells of migrating to the US as a small child, serving in the military, and getting deported at age 66 in his digital story “The Life of a 73-Year-Old Deported Army Veteran”; he returned to the US at age 77 in 2021.

Unlike these three lucky migrants, the vast majority, including both those who had been undocumented and those who lost their permanent residency, have no means of returning legally to the US. Although the Biden administration has sought humanitarian relief for a few, as was the case with Andy de León, without a change in laws, some may never see their families in person again.