Central American Migrants and Asylum Seekers

By Robert McKee Irwin

Problem

Since the arrival of the migrant caravans of late 2018, the US has implemented a number of policies to deter the arrival of asylum seeking migrants from Central America at the US’s southern border, forcing them to wait for months or even years in Mexico for their cases to be evaluated. Notwithstanding the unprecedented severity of these policies, large numbers of asylum seekers are gathering at the border, many with expectations that may not align with the reality of their chances for obtaining asylum. US law requires applicants to demonstrate “a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion,” criteria that have not been easy to prove in these terms for Central Americans, whose asylum cases rarely succeed – less than 10% end positively for migrants from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras, according to 2017-19 Department of Homeland Security figures. In absence of any clear statements on new revisions of asylum assessment criteria, it is seems likely that the vast majority of those currently waiting admission in Mexican border cities will end up getting deported back to their home countries. Yet many do face real dangers.

Solution

The US must establish a humane system for receiving asylum seekers at its southern border, and for processing asylum applications efficiently and fairly. All US immigration agents must be trained to treat all arriving migrants humanely. Furthermore, criteria for evaluating asylum claims should be reviewed to ensure that international human rights protocols are honored. At the same time, migrants should have access to accurate information on of the kinds of experiences that justify political asylum in the US and the kinds of evidence required for a successful application in order to ensure that applicants have a legitimate possibility of being granted asylum.

Observations

Several stories from the Humanizing Deportation archive help to illustrate different dimensions of the problem.

One anonymous asylum seeker explains in his digital story, “El Vato, Fighting for a Dream for My Son,” that he left his native Honduras due to “lack of employment,” yet hopes to obtain political asylum. He adds that he is determined not to return home: “I want to give my son a future, I want to help my Mom and Dad.” Given this story, he would probably be judged an economic migrant, his asylum case summarily denied.

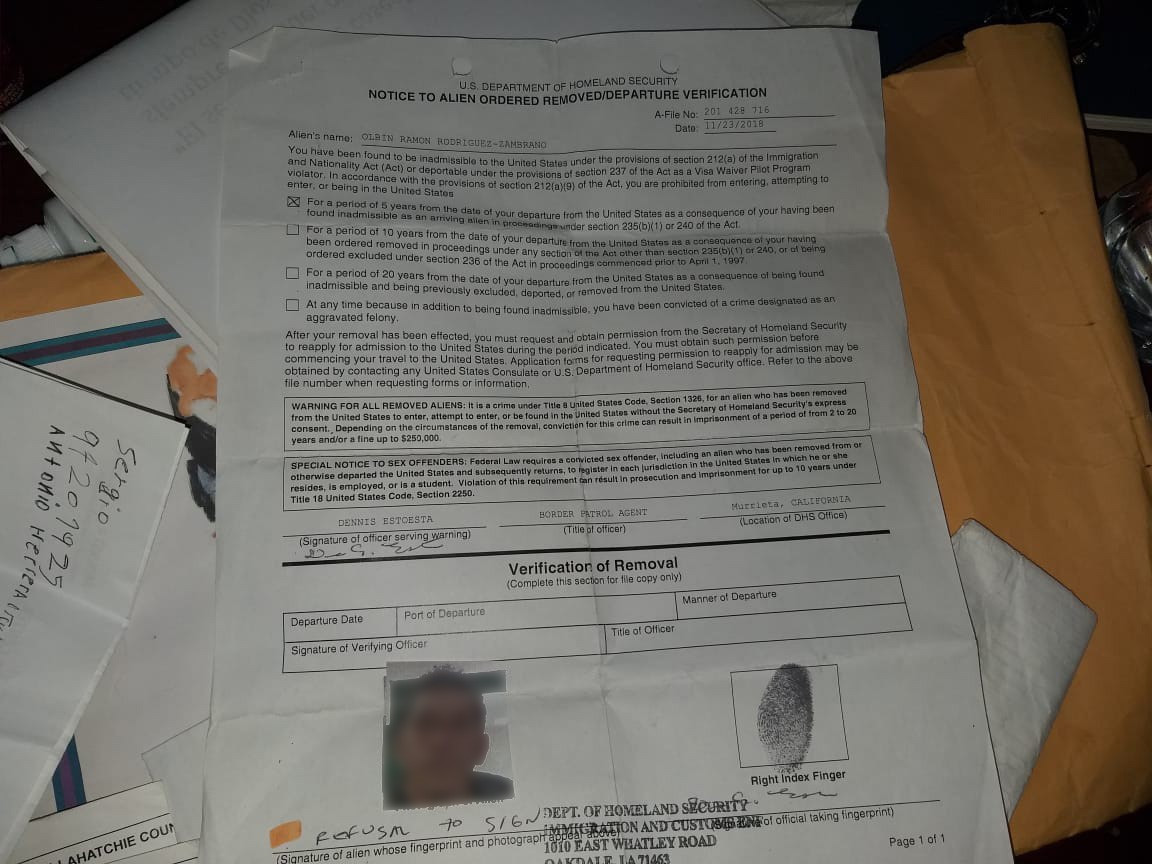

Another anonymous Honduran migrant, who traveled to Tijuana in one of the Fall 2018 caravans, explains in the second of a two-part digital story, “After the Caravan,” that he had to close his small business, an auto repair shop, due to threats from organized criminal groups, who insisted that he pay them a “tax” that he couldn’t afford. Since mid-2018, following instructions from the US Attorney General’s office, many claims for asylum based on threats of gang related violence have been routinely dismissed for not adhering to a narrow interpretation of US law (see above). When this migrant presented his story to a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agent, he was denied the opportunity to file his asylum case and was furthermore instructed to sign a voluntary removal form. When he refused, he recalls: “they insulted me, they told me that I looked like a delinquent.” They then screamed obscenities in his face and “got rough with me.” Three agents “grabbed my hands and bent me backwards,” forcing him to put a fingerprint onto the form, which they then used to deport him.

Unfortunately, he was never given the chance to tell his whole story. Another reason why he left Honduras was that he had witnessed a kidnapping, and then agreed to testify as a witness for the state. He assumed that his safety would be ensured, but, as he tells it in the first installment of his story “From Inside the Caravan”: “no, they put the person I was testifying against right in front of me” and then denied him police protection. While his was not a case of political persecution, the complicity of the state in putting his life in danger should have made his case worthy of consideration from an asylum officer. Asylum officers are supposed to be trained to allow applicants the opportunity to offer any information they believe relevant to their case, and not to interrupt their interview as the border patrol agent interviewing this migrant did. In addition, had they not forced his fingerprint onto a voluntary removal form, they would have had to file deportation papers against him, which would have given him the opportunity to appeal his case before an immigration judge.

He was lucky. After being deported, he immediately left Honduras again, this time with his pregnant wife and young son; before they made it back to the US border, their baby was born, allowing the family to apply for legal residency in Mexico.

Another Honduran migrant, who ultimately did obtain asylum in the United States, Douglas Oviedo, in the third installment of his four part digital story, “Stories from the Caravan,” recalled that upon crossing for the first time into the United States, the CBP agent that received the group that entered that day immediately demanded to know which ones were from Central America; Douglas confirmed that “they had something against Central Americans” later when Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents “started saying offensive things against Central Americans."

While the first case may offer some insights into why so few Central American asylum cases get approved – i.e., many asylum seekers may not realize that their cases do not align with criteria used to evaluate them, the second demonstrates that the culture of hostility toward Central American migrants within federal immigration agencies may make it impossible for many to get a fair hearing. Hopefully the Biden administration will promptly enact new policies for processing asylum claims, including better training of immigration agents, to ensure that asylum cases are evaluated promptly, and not dismissed without a fair hearing.