Intergenerational Mobility of Immigrants in the US Over the Last Two Centuries

By Santiago Pérez

The Facts:

- Children of poor immigrants from nearly every sending country have had greater success climbing the economic ladder than children of similarly poor fathers born in the United States.

- Children of poor immigrants today are no slower to move into the middle class than children of immigrants from 100 years ago.

The Data:

A defining feature of the “American Dream” is the view that even immigrants who come to the United States with few resources have a real chance at improving their children’s prospects. In a working paper (joint with Ran Abramitzky, Leah Boustan and Elisa Jácome), we use millions of father-son pairs to answer two related questions:

- Are children of immigrants more likely to move up in the economic ladder than children of natives from similar economic backgrounds?

- Are children of contemporary immigrants more or less likely to move up in the economic ladder than children of immigrants from 100 years ago?

Our analysis encompasses three groups of immigrants: The first two groups consist of first-generation immigrants observed with their children in either the 1880 or 1910 US Censuses. Immigrants in these two groups were predominantly from Europe and came to the country in an era of nearly open borders for European immigration. We follow their sons to the 1910 and 1940 Censuses, respectively. Because pre-1940 census do not include information on earnings, we construct income scores (based on an individual occupation) to measure economic outcomes. In these data, we are only able to follow sons from their childhood homes into adulthood, given that daughters often change their names at marriage. Thus, for consistency, we focus on father-son pairs throughout the analysis.

The third group includes immigrants who came to the US around 1980, largely from poorer countries in Latin America and Asia. Immigrants in this era faced a much more restrictive migration policy regime than those in the previous two groups. We are able to observe earnings data of fathers and sons in this cohort, thanks to publicly available data compiled by Opportunity Insights. Importantly, however, the Opportunity Insights includes only authorized immigrants. Hence, we complement these data with information from the General Social Surveys (these data also enable us to use occupations to measure economic outcomes, thus facilitating the past-present comparison).

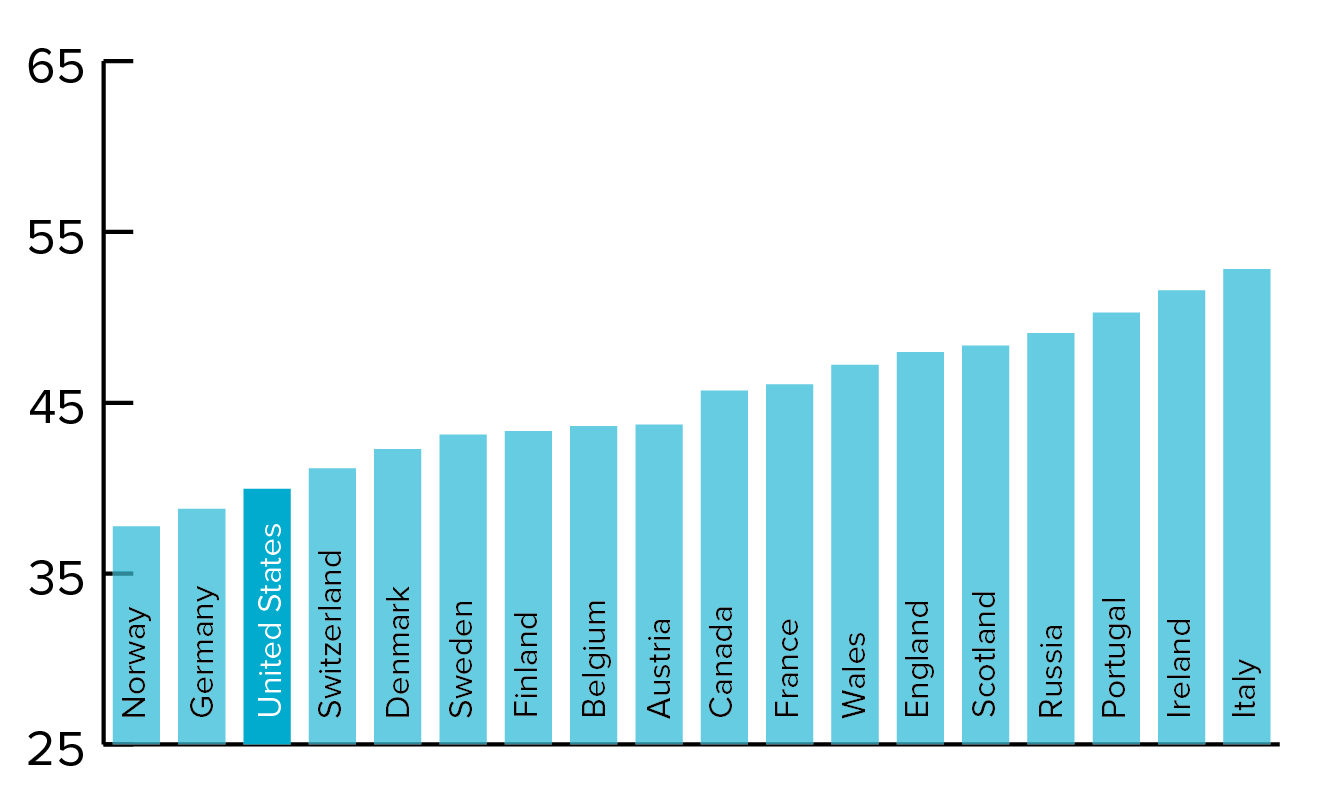

The figures show the expected adult rank of sons who grew up in families at about the 25th percentile of the income distribution in the US. Each bar corresponds to a different country of origin, based on the country of birth of a person’s father. Figures (A) and (B) focus on the immigrants who came to the US during the late 19th century and early 20th centuries, whereas figure (C) focuses on the most recent immigrant wave.

There are two main takeaways from this set of figures. First, both in the past and today, children of immigrants from nearly every sending country have a higher expected rank in the income distribution than children of the US born from similar economic backgrounds. This finding indicates that the children of immigrants have been more likely to move up in the economic ladder than the children of the US born. Second, children of contemporary immigrants move up in the economic ladder at similar rates than children of immigrants in the past. For instance, the adult children of poor immigrants from Mexico today achieve a similar rank in the income distribution than the children of poor immigrants from Finland or Scotland in the past.

What Does this Mean for the Economy and for Policy?

One main implication of these facts is that a short-term perspective on immigrant assimilation might be misguided: there is substantial progress by the second generation. Overall, our analysis suggests that focusing beyond the first generation yields a more optimistic view about the long-run economic success of immigrant families.

A second implication is that a “nostalgic” view on immigrant assimilation might also be misguided: Despite dramatic changes in the countries of origin of immigrants (from Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to Latin America and Asia more recently) and in US migration policy, children of immigrants today move up in the economic ladder at a similar pace than the children of those who came to the country more than 100 years ago.