Police Harassment of Deported Migrants

By Robert McKee Irwin

Problem

Mexican migrants may have difficulties reestablishing their lives in Mexico following a deportation. While their rapid integration would undoubtedly be of benefit not only to migrants themselves, but to Mexican society at large, Mexican governmental agencies are rarely helpful in this process. Mexican police have been especially problematic in this regard. They often target deported male migrants, harassing, extorting, beating and jailing them without cause, thus making these migrants’ transition to living productive lives in Mexico especially difficult.

Solution

Repatriated migrants should be encouraged to report police abuse to Mexican human rights authorities. Mexican human rights authorities should investigate complaints of police harassment and brutality toward repatriated migrants, and should monitor police in areas in which complaints are registered frequently. Police officers and their superiors should be held accountable for improper actions. US authorities should avoid deporting nonviolent migrants, especially childhood arrivals, who are easily identifiable and likely to be subject to police harassment in Mexico.

Observations

As noted in our previous installment of Migrant Narratives, deportation is often a traumatic event in migrants’ lives. It often takes months or years for migrants to adjust to their post-deportation circumstances, which may include family separation, loss of income or property, and feelings of failure or shame.

Deportations from the United States to Mexico have over the past two decades increasingly included migrants who have lived many years in the United States. The establishment in 2003 of Immigration Customs and Enforcement (ICE), an agency charged with police powers to detain and deport migrants in the interior of the country, and this agency’s rapid growth, has led to large increases in deportations of migrants who have not recently crossed the border. These migrants often have deep roots in the US, including job, family, and in many cases major assets such as a house or a business.

Aside from psychological barriers to adjusting to forced displacement, and logistical obstacles, including difficulties in obtaining identification papers needed for employment, police harassment of deported migrants is frequent. Migrants who have lived a long time in the US may be identifiable by styles of dress, tattoos, or sometimes backpacks. Migrants staying in shelters in border cities such as Tijuana are often required to check out every morning, and must take all their belongings (usually not much more than clothes, telephone, personal papers) with them, typically in backpacks, until they are allowed to check in again in the late afternoon.

Police target them, extorting what little money they may have, sometimes beating them, often confiscating their personal papers and other items, and sending them to jail for a few days without any clear charges. Unjustly incarcerated migrants who may actually have jobs may lose them when they fail to show up for work. Alberto Espinosa (pseud.) recounts his experiences with the Tijuana police in his digital story, “Deported Mexicans and Tijuana Police: Abuses and Violences”, emphasizing the difficulties he faced in maintaining employment due to their constant harassment.

Early in the decade of the 2010s, large camps of deported migrants formed along the border in the mostly dry canalization of the Tijuana River, a site popularly known as El Bordo. A thousand or more migrants concentrated there in clusters of lean-tos (locally known as “ñongos”) or burrows dug into the riverbed, and sewage conduits that empty into the canal. These very large numbers of migrants elected to live there despite the unsanitary conditions and exposure to the elements in part because they felt safe from police harassment. However, as the camps grew, they attracted the attention of global media, and Tijuana’s municipal police began a sometimes violent campaign of removal.

Guadalupe Mendívil, who himself was not deported, but lived for a number of years in El Bordo while addicted to drugs, offers his own observations on the massive arrival of deported migrants to these homeless camps, and the often brutal tactics deployed by authorities to clear them out in the second and third parts of his three-part story “Thanks to the Deportees, Another Chance” (Part 2 and Part 3).

Ignacio Davis, a deported Mexican who also lived for a time in El Bordo, describes the experience of everyday life there in his digital story, “Surviving El Bordo”. He also recounts the campaigns to clean out the canal, which was carried out with a ruthlessness that likely led to the deaths of some of the migrants.

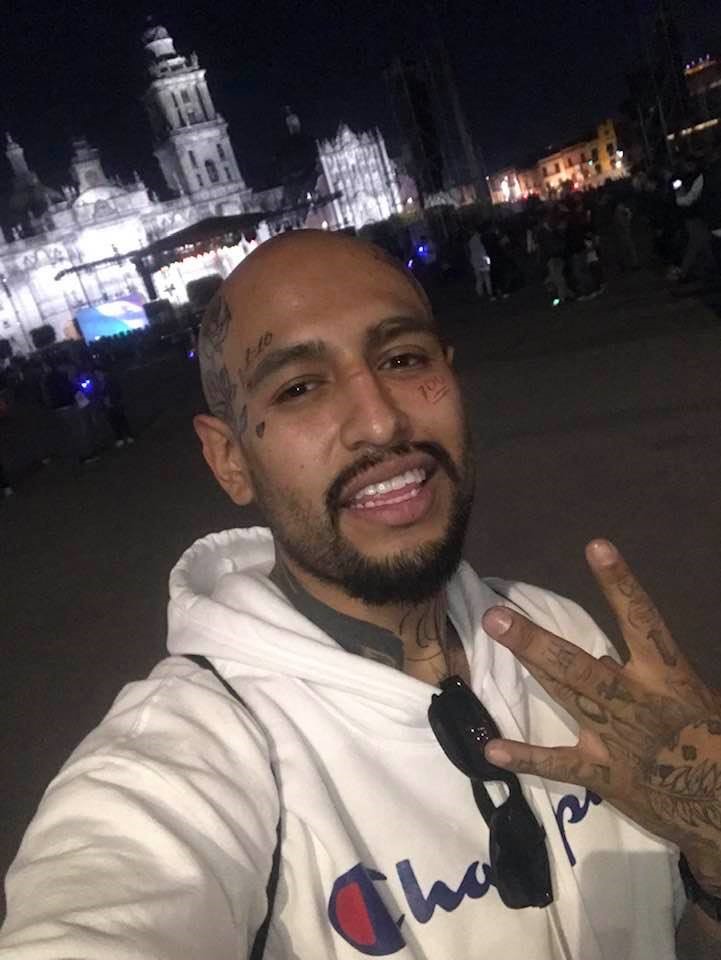

Police harassment of deported migrants is not limited to Mexico’s northern border cities, where the vast majority of deportations occur, but are also common in Mexico’s interior. Christian Guzmán, a childhood arrival who lived most of his life in Oklahoma whose accent, style of dress, and tattoos identify him as having grown up in the United States, refers to incidents of harassment in both Puebla and Mexico City, where police officers stop him on the street without cause, sometimes beating him, threatening to plant drugs on him, or demanding bribes, in his two part story “Forced Out of My True Home” (Part 1 and Part 2).

Together these stories show that many deported Mexicans face institutional hostility and indifference that may make it difficult or impossible to accommodate themselves to their new situation, and whose consequences may sometimes be extreme.